HOW SUPER BOWL III BEGAN WITH JOE NAMATH

The Super Bowl began with Joe Namath. Nit-pickers will point to Vince Lombardi, whose Green Bay Packers won the first two games in the series between the champions of the National Football League and the American Football League. Technically, that is correct. But the Packers won those two games with such remarkable ease, defeating Kansas City 35-10 and Oakland 33-14, that there was little drama. It was men versus boys, times two.

The Game did not become The Event until Namath led the New York Jets to a 16-7 upset of the Baltimore Colts in Super Bowl III. Broadway Joe, the roguish quarterback whose talent was exceeded only by his swagger, brought some welcome spice to the championship game. Millions flocked to their television sets to watch. Thirty years later, they still are watching.

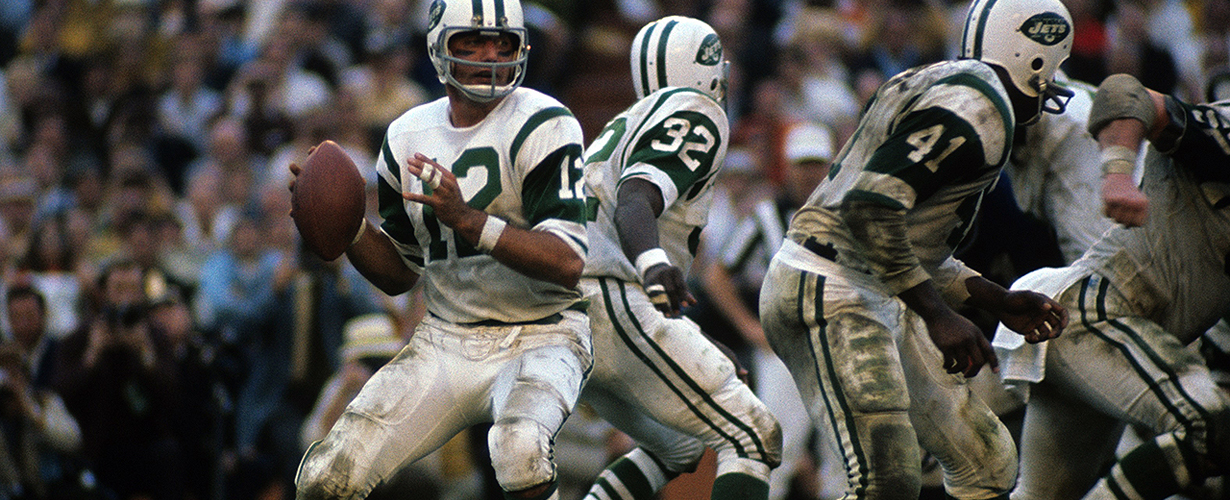

Joe gets under on center during Super Bowl III in 1969.

Joe threw for 206 yards in Super Bowl III.

“I don’t know that a day goes by that I don’t get reminded of that game,” Namath says. “I never get tired of talking about it. It’s a memory that never gets old.”

The Jets, AFL champions with an 11-3 regular-season record, were 19-point underdogs to Baltimore. The Colts, coached by Don Shula, dominated the NFL with a 13-1 regular-season record and crushed Cleveland 34-0 in the NFL title game. The Colts had the top ranked defense in the league and were considered one of the great teams of all-time. As the odds reflected, most people felt the NFL was vastly superior to the AFL. Green Bay’s easy victories over the Chiefs and Raiders only reinforced that belief. The NFL, with roots tracing back to 1920, was seen as the one true professional league. The AFL, born in 1960, was regarded as a pale imitation.

On the eve of the big game, former NFL quarterback Norm Van Brocklin was asked for his assessment of Namath. Van Brocklin, who would be inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame in 1971, was head coach of the Atlanta Falcons at the time, and he was a firm believer in NFL superiority.

“I’ll tell you what I think about Joe Namath on Sunday night — after he has played his first pro game,” Van Brocklin said.

The Falcons’ coach spoke not only for NFL loyalists but also for millions of people around the nation who did not believe in any player or team with an AFL pedigree.

To a man, the Jets were irritated by that lack of respect, but none took it as personally as Namath. On Thursday night before the game, Namath was honored by the Miami Touchdown Club as its player of the year. As he stepped to the microphone, a voice in the crowd-belonging to a Colts’ fan, obviously-called out: “Hey, Namath, we’re going to kick your ass.”

Most of the audience laughed. Namath didn’t.

“I said, ‘Whoa, wait a minute. You guys have been talking for two weeks now’ – meaning the Colts’ fans and the media — ‘and I’m tired of hearing it,’” Namath remembers. “I said, ‘I’ve got news for you. We’re gonna win the game. I guarantee it.’ “I didn’t plan it. I never would have said it if that loudmouth hadn’t popped off. I just shot back.

"I’ve got news for you. We’re gonna win the game. I guarantee it."

Joe NamathWe had a good team, but people were treating us like we didn’t belong. I was fed up with it and I guess it just came out.”

It was not until he sat down that Namath realized what he had done. He had guaranteed a victory. Surely, this would be the lead story in every newspaper and on every television sports show in the country. Those who regarded him as an arrogant loudmouth — and many people did — had more reason than ever to root against him.

Namath’s supporters happily applauded his bravado. One thing was certain: Come Sunday, they all would be watching. When Namath returned to the hotel, he called cornerback Johnny Sample, the Jets’ defensive captain, in his room.

“Joe told me, ‘I said something tonight that’s gonna be all over the news tomorrow,’” Sample says. “I asked him: ‘What the heck did you say?’ He told me he guaranteed we’d win the game. I said, ‘Man, you didn’t say that.’ He said yeah, he did.

“The thing was, we all thought we’d win the game. We had studied film on the Colts and we were confident. But a guarantee? Joe said, ‘Well, we’re gonna win, aren’t we?’ I said, ‘Yeah, Joe, we’re gonna win, but you shouldn’t have said it.’”

Jets coach Weeb Ewbank knew nothing of Namath’s comments until the next day when he awoke to find the “guarantee” bannered across the front page of the morning paper. He was absolutely furious. He had instructed his players to lavish praise on the Colts and, if possible, make them even more overconfident. Namath’s outburst, he feared, jeopardized everything.

“I asked Joe what possessed him to do such a thing,” Ewbank said. “I said, ‘Don’t you know Shula will use this to fire up his team?’ Joe said, ‘Coach, if they need press clippings to get ready, they’re in trouble.’ “I could have shot him for saying it. But Joe always had a way of delivering. He didn’t mind pressure. It seemed to make him play better. I figured, if he said it, he would just have to back it up.”

Playing before a capacity crowd at the Orange Bowl, with millions more watching on television, Namath coolly dissected the mighty Colts. He exploited the right side of Baltimore’s defense, where age had slowed end Ordell Braase (36), linebacker Don Shinnick (33), and cornerback Lenny Lyles (32).

With his quick release, Namath beat the Colts’ blitz with quick passes to split end George Sauer (8 receptions, 133 yards). The brash 25-year-old quarterback proved to be every bit as good as advertised — and much better than the Colts bargained for.

“We studied the film [of Namath], and we knew he could throw the ball, but we felt we could pressure him,” Shula says. “Our blitz dominated the NFL that season. We put eleven people on the line, and sometimes we’d send them and other times we’d drop into coverage. We never thought Namath, facing that for the first time, would handle it as well as he did.”

“We had a system called ‘check with me,’ which meant I called most of the plays at the line,” Namath says. “We got in and out of the huddle in a hurry so I’d have more time to look things over. If you look at the films, you’ll see how many times I made a call, saw something [in the defense] and changed off. It looks like we’re up there over the ball forever. But that’s where we made our calls.

“Another thing you’ll notice is, I kept my hands under center the whole time. I wanted to keep the pressure on the defense. I wanted them to think the ball could be snapped at any time. It was a subtle thing, but it was one more thing to keep them off balance. If they had a blitz on, I’d see the linebackers and safeties edging up, trying to get a jump, getting frustrated.

“I felt we had an advantage because the Colts were in a Catch-22 situation. They had this defense that had killed the whole NFL that season. Why should they change for one game against a nineteen-point underdog? So I knew they were going to stick with the same fronts, the same coverages, the same blitzes. It was like having all the questions for an exam two weeks before you actually take it. By the time we played, I knew those guys inside-out.”

Namath directed the Jets’ offense with patience and precision. He mixed his passes with the powerful runs of fullback Matt Snell (30 rushes, 121 yards) as the AFL upstarts took control of the game.

The Colts could not generate any points with quarterback Earl Morrall. By the time Shula brought sore-armed Johnny Unitas off the bench in the third period, the Colts trailed, 13-0. The Jets were in such complete command, Namath did not have to throw a single pass in the fourth quarter. He simply ran out the clock.

Joe brought the Jets their first and only Super Bowl Championship

The Jets brought the AFL its first Super Bowl victory and the stature needed to validate the merger of the two leagues, which was agreed upon in 1966 and finally completed in 1970. It was a watershed moment in the history of pro football, and Broadway Joe’s star power put the Super Bowl at the top of the American sports marquee. Namath’s numbers were unspectacular by his standards (17 completions in 28 attempts for 206 yards), but he was such a commanding figure that he was voted the game’s Most Valuable Player. Through the first 34 Super Bowls, 18 quarterbacks have been named Super Bowl MVPs, but Namath is the only one to win the award without passing for at least one touchdown.

As Sample says, “Everything that happened that day revolved around Joe.” Indeed, everything about that game still revolves around Joe. It was his stage, his moment. It defined his career. He was voted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame in 1985 almost entirely on the impact of that game. It hardly matters that he had only three winning seasons with the Jets, or that his career interception total (220) far exceeds his number of touchdown passes (173). What matters is the image of Broadway Joe trotting off the field, waving his index finger in the Orange Bowl twilight, and reminding everyone that the Jets were number one.

“We touched a lot of people’s lives,” Namath says. “I can’t tell you how many times I have had people tell me they used our win as a motivating force. Teachers, coaches, everyday people. The moral is the same: If the Jets did it, you can do it. “We sent a message to all the underdogs out there. If you want something bad enough and you aren’t afraid to lay it on the line, you can do it. It’s an important message because if people don’t have hope, really, what do they have?